Posted on: May 5, 2022

Walk the tightrope: Drive performance & support mental health

You become aware that a crucial member of your team is falling behind. They have been taking longer to complete their tasks, are making more mistakes, and are f...

By Shivekiar Tashchioglu

You become aware that a crucial member of your team is falling behind. They have been taking longer to complete their tasks, are making more mistakes, and are feeling overwhelmed with their workload which they had been managing well before.

As a leader, you ask yourself the question; what do I do?

Their performance has been derailing the team’s progress, as they are slowly starting to become a bottleneck. Others have been feeling the increasing pressure to keep on track. You know you need to take action quickly.

But, you’re also aware that this person hasn’t seemed their usual self recently. A conversation reveals your instinct is correct. They explain they’ve been suffering from a bout of depression that’s been affecting their ability to concentrate and work effectively.

You want to be there to support them. Yet, you also know you have a responsibility to the company to deliver on pressing results.

Walking the tightrope between performance & mental health

Welcome to one of the most difficult dilemmas you can face as a leader.

Leaders are encouraged to create workplaces that support the mental health of our employees – and yet at the same time, run a business that has objectives to meet. Many workplaces have adopted performance-management processes that focus on intervening only when an employee is not performing as expected.

It’s very important to address and resolve what is not working, but focussing on the negative tends to reduce the motivation of the employee (and often the leader as well). In the case that the employee is experiencing mental health issues, there’s a risk that this approach may worsen both their symptoms and work performance.

You are not alone

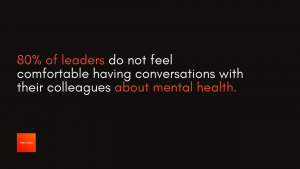

We know a lot of leaders struggle with this. According to a research piece by Interact (2022), 69% of managers report feeling uncomfortable communicating with employees in general, and around 80% are not comfortable having conversations on mental health with their colleagues (Protectivity, 2019).

It is much easier to notice and address the visible, than the invisible. It comes as no surprise then, that leaders often follow the prescriptive performance management processes – tackling the performance challenges head-on without first questioning the underlying mental health challenges. They are, after all, short on time, capacity, and confidence.

But the latter can change. Nobody is born a master of such conversations, this is a skill to be learnt. This is a skill we are teaching at Feel Good.

Advice from our flagship programme for leaders, Brilliant Minds, can help to address this challenge

Often we hear from leaders during coaching sessions that when they spot the signs that someone is struggling, they often hesitate in taking action. Sometimes they are afraid of saying the wrong thing, doing the wrong thing, or opening up a conversation they feel underqualified to handle.

Supportive conversations, however, aren’t about fixing or problem-solving. They are about creating an environment in which the other person can process their emotions, get their thoughts in order, and identify the right solution for them.

Bringing the conversation to life

If we are to effectively support people, it has to start with a conversation. This is a chance to find out how they feel, their concerns, what matters to them, and why. It involves sharing power with them and ultimately uncovering their unique motivations for change.

Asking the right questions

We need to start by getting ourselves into a situation where we can ask the right questions. For all sorts of reasons, this is not always straightforward. Keeping the scenario above in mind, below are some examples that help:

- I would like to have a conversation about how things are for you at the moment so that we can ensure we are here to support you in any way we can.

- I know you have a lot on your plate right now and you’re supporting a lot of projects. I wanted to check in and ask how you are doing?

- You say you’re OK, but I notice you are more distracted than usual. I’m wondering what is troubling you so much?

If you have gently tried to encourage them to talk and they still don’t want to, that means they don’t want to (for whatever reason). It is important to respect this.

Setting up the context: Timing

Consider the timing of the conversation with the individual – is there something about the timing that isn’t going to encourage them to open up? Are they trying to hold themselves together so they can get through the working day? Ask them when would be the best time to have this conversation For some people, it’s the start of the day, for others it’s the end of the day when they can switch off afterwards to process what has been discussed.

Setting up the context: Space

If you are both in the office, consider moving to a quieter part of the office or better, going on a walk outside. Sometimes being on the move can make it easier for an individual to open up.

If you are working remotely, consider whether a video conversation is necessary to get your point across. Individuals often find it easier to open up and share their ideas whilst on a phone conversation.

Confidence of the individual is just as important as your own confidence to ensure you can get the most out of the conversation moving forward.

Setting up the context: Your image counts

Your body language speaks volumes. Avoid these micro-behaviours that break trust:

- Forgetting to smile

- Fidgeting

- Having conversations whilst standing up (easily perceived as time short or dominating)

- Crossing arms, legs or slouching (easily perceived as less friendly or even rejecting)

- Tapping your feet (easily perceived as impatient, anxious or irritated)

- ‘Hiding behind’ physical barriers

- Too much eye contact (easily perceived as threatening or superior)

- Too little eye contact (easily perceived as inattentive or insincere)

- Blocking the exit

Something to consider: Those with ADHD, Autism or other neurodiversities are far more likely to show some of these signs unintentionally. This does not mean you/they are not listening.

Replying with care

More important than saying the right thing or knowing the ‘answer’ of how to fix the problem, is the ability to build the conversation in a way that creates the right environment – one of psychological safety and support.

The person with the problem invariably has the solution but needs you to create the conditions for them to find it. This is containment – creating an atmosphere of safety which allows the person to move through their emotions and reach a place they can think more clearly.

Your job is to be a sounding board, not a sponge. To do this, focus less on what to say, and more on how you choose to be with them to set the right tone.

- Reflect – repeat the person’s words back to them exactly as they said them

- Paraphrase – rephrase what you think the person has said but in your own words

- Clarify – use an open question to make sure you fully understand what is meant

- Summarise – condense the most important points of the conversation (usually at the end)

Conclusion

Think about your marginal gains. Small changes to the questions you’re asking and the responses you are giving can create a very meaningful impact.

And remember, you don’t have to solve anything. When the ‘problem’ you are dealing with is somebody else’s emotions or behaviours, you cannot go into fixing mode. Emotions and behaviours aren’t fixable in the same way that physical things are.

You can fix a person’s broken washing machine, but not their mental health or performance. You stand a much better chance of helping them if you give them the space, the time, and a little nudge to find their solutions themselves.

Our flagship programme for leaders, Brilliant Minds, is the brainchild of the brilliant minds of our clinical and business psychologists. This programme is designed to empower leaders to walk the tightrope that is having conversations surrounding performance and mental health.

Blending theatre, coaching, and cutting-edge research in psychology, this programme helps you to build marginal gains with practical tips to build your confidence. Explore a range of evidence-based skills and techniques that will provide a solid foundation for such courageous conversations.

PSYCHOLOGY-POWERED SOLUTIONS THAT DRIVE IMPACT

Feel Good evolves how your people think, feel and perform with strategic thinking and engaging learning solutions powered by the latest organisational & behavioural science.